with Michael Hansmeyer

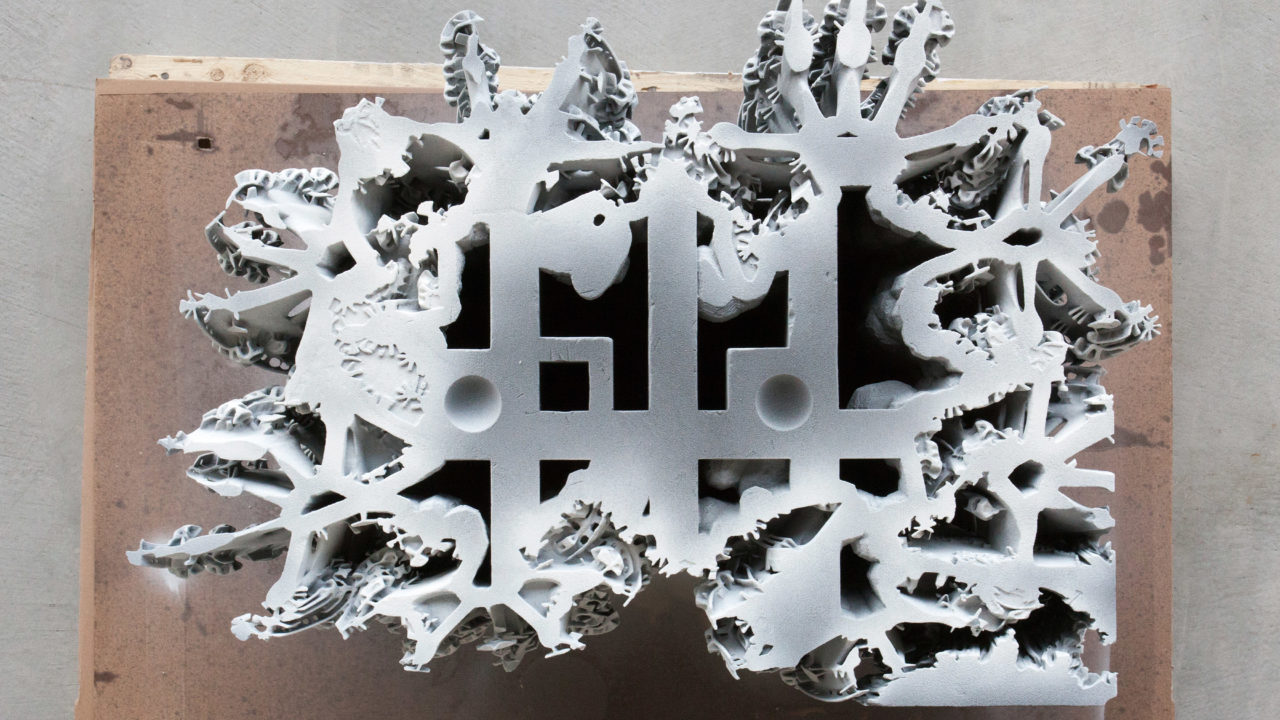

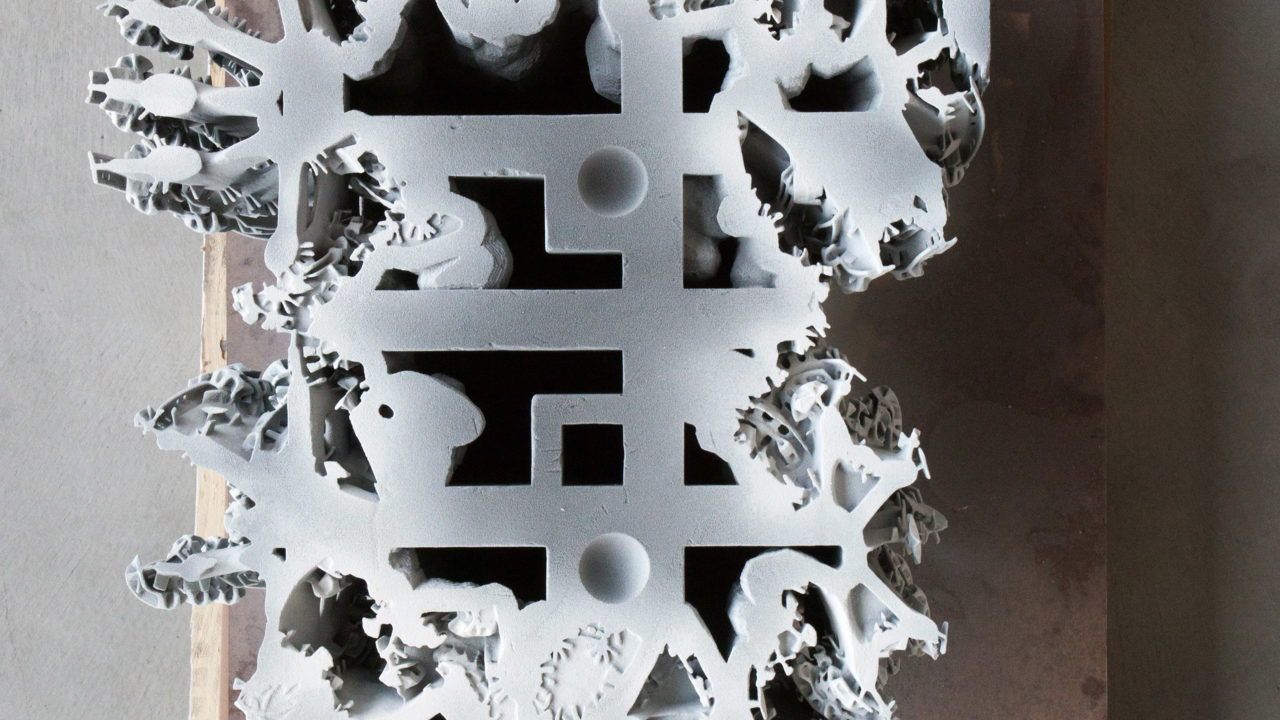

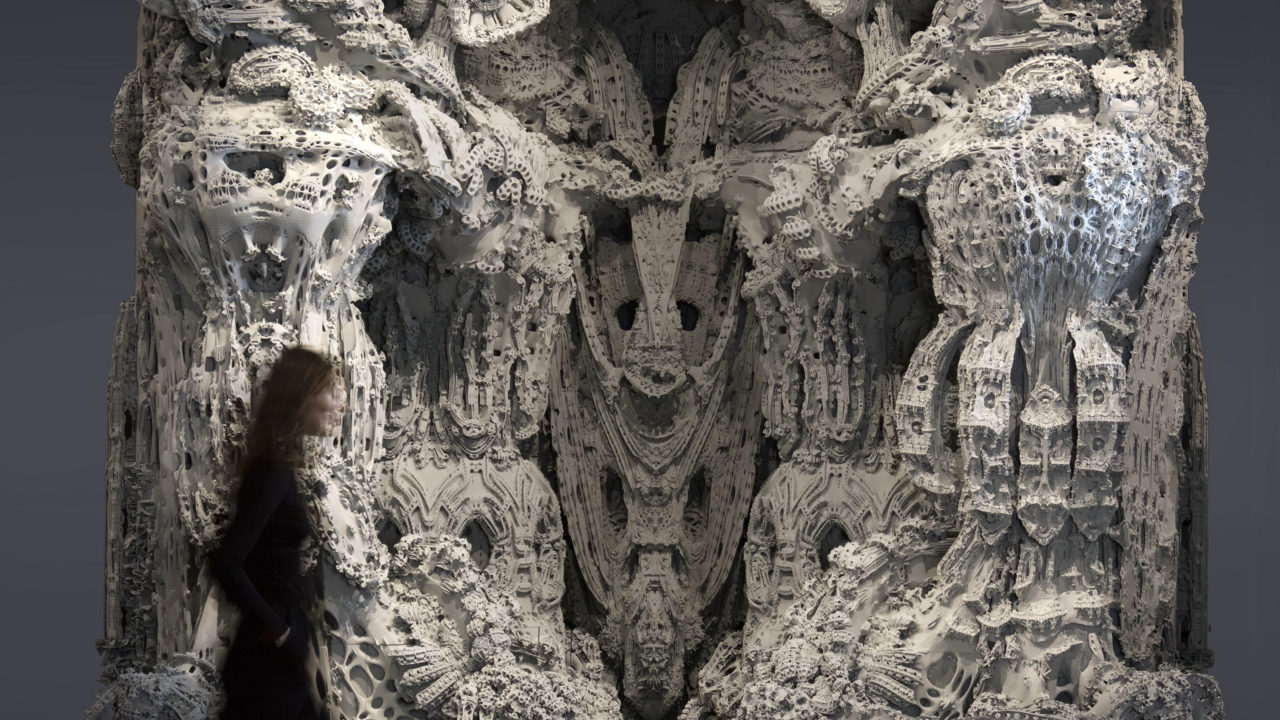

Digital Grotesque II – a full-scale 3D printed grotto – has premiered at Centre Pompidou’s ‘Imprimer le monde’ exhibition. This highly ornamental grotto is entirely designed by algorithm and materialized out of 7 tons of printed sandstone. It heralds a highly immersive architecture with a hitherto unseen richness of detail.

The angles and perspectives by which the spectator can observe the grotto were simulated during the design process, and the form was then optimized to present highly differentiated and diverse geometries that forge a rich and stimulating spatial experience for the observer.

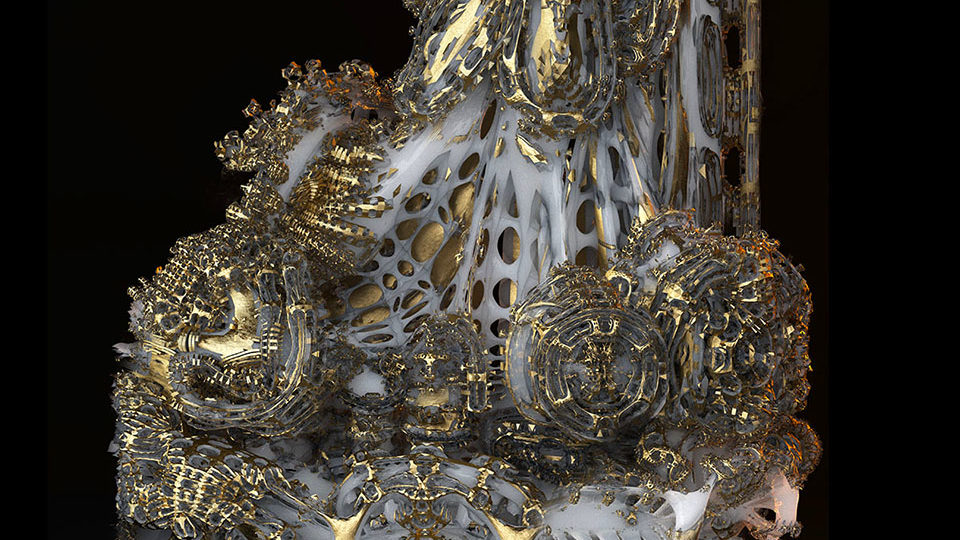

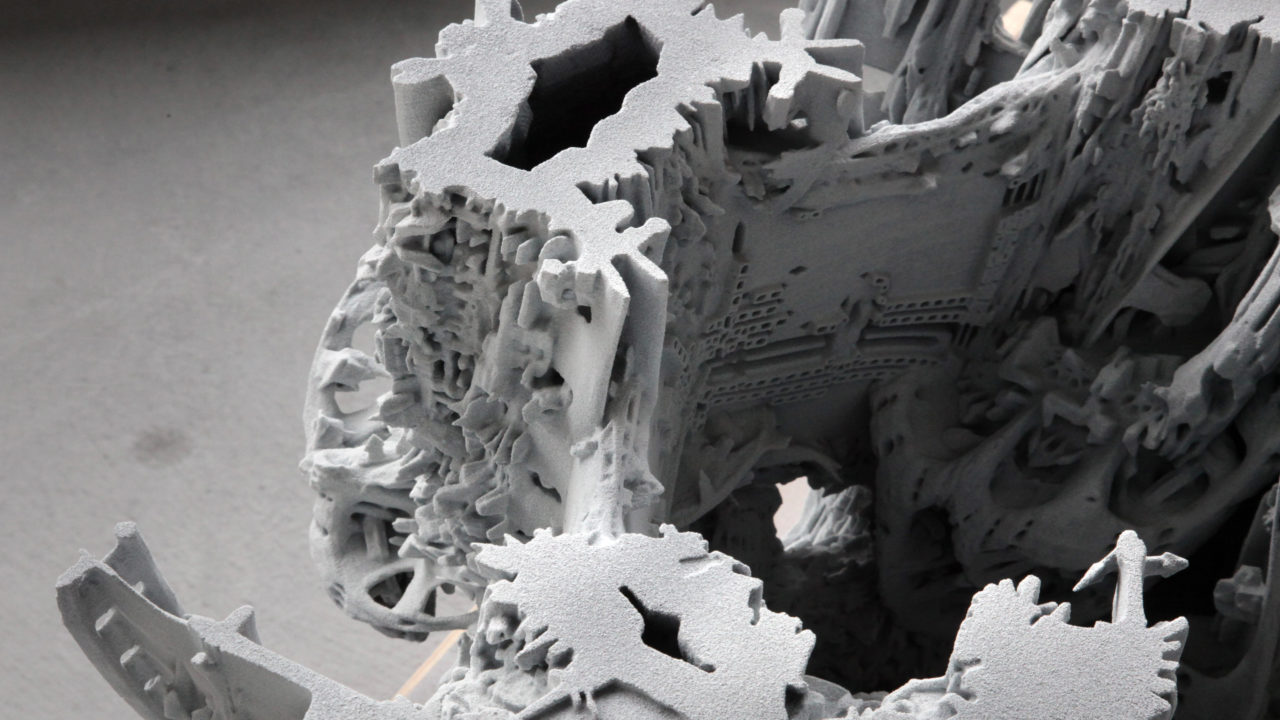

A subdivision algorithm was devised to exploit the 3D printer’s full potential by creating topologically complex, porous, multi-layered structures with spatial depth. A single volume spawns millions of branches, growing and folding again and again. Hundreds of square meters are compressed into a 3.5m high block that forms an organic landscape between the man-made and the natural.

Digital Grotesque II is a testament to and celebration of a new kind of architecture that leaves behind traditional paradigms of rationalization and standardization and instead emphasizes the viewer’s perception, evoking curiosity and bewilderment.

K&G Studio

Can we fabricate more than we can design?

Today, it appears we can fabricate anything. Digital fabrication now functions at both the micro and macro scales, combining multiple materials, and using different materialization processes. Complexity and customization are no longer impediments in design.

While we can fabricate anything, design arguably appears confined by our instruments of design: we can only design what we can directly represent. Are we unable to exploit the new freedom that digital fabrication offers us?

In Digital Grotesque II, we sought to develop new design instruments. We viewed the computer not as parametric system of control and execution, but rather as a tool for search and exploration. The computer was a partner in design who proposed an endless number of permutations, many of which were unforeseeable and surprising. Further, the computer was able to evaluate its generated forms in respect to an observer’s spatial experience. It learned to evolve these forms to maximize their richness of detail and the number of different persepctives they offered.

As of yet, we’ve been using computers to increase our efficiency and precision. Why not see them as our muse, as partner in design, or as a tool to expand our imagination? Digital Grotesque II pursues these directions.